A still-active strand of the Tea Horse Road in northwestern Yunnan province where that relentless editor 'time' has changed very little...for now. Caravans still transport goods into remote portions of the mountains. Taken upon our journey along the route in 2006

Much of the Tea Horse Road’s great appeal is the sheer expanse of geography taken in – some estimate (as we did when our team traveled it) that five thousand grand kilometres taking in rafts of culture, language, diet, altitude and of course risk. Rather than one route or ‘road’, the Tea Horse Road might be better called the Tea Horse ‘Roads’ – a grand series of paths, directions, and wisps that bonded, spread and spiraled away before once again coming together. Cultures along the route are – as they were – one of the great enriching elements – a spray of minorities, majorities and hidden peoples all involved in some way in what many traders referred to as the ‘eternal road’. Traders who traveled the route (and lived to tell) were often viewed in a kind of awe – they were mortals who had ‘seen’ other lands, tasted other food…and survived. The Tea Horse Road (chamadao) moniker only really came later during the Song Dynasty – at which time (and not by accident) a tax was also developed. Detailed accounts of trade items and their worth were written down and in effect the ‘numbers’ story of the route became eternal.

Wonderfully tangible where commodities, transporters and traders are all in the mix the caravan system is fast becoming something of the past. Taken on our journey near the town of Ala Jagung in eastern Tibet.

Tea was a rampant fixation for the mountain peoples of the plateau (many guess) long before its ‘official’ introduction by Princess Wenchang upon her betrothal to the all-powerful unifier of Tibet, Songtsam Gambo, of the seventh century. Teas were not only traded along the entirety of the route – teas were consumed in any number of manners, used to sate, to cure, to counter and to feed. Though the methods of preparation differed, the leaves conceivably were the same.

The Hani, Pulang, Wa, Dai and Lahu all populate the southern tea strongholds of southern Yunnan, though few if any would have traveled as far as their tea offerings did along the tea routes. Here a Hani woman near Banzhang.

Stretching back in time, beyond the ‘Tea Horse Road’ title, a route was already humming along between the great empires of Yunnan (though then, not ‘Yunnan’) and the Tibetan Plateau. The Tea Horse Road to the rugged mountain peoples was known by the name Gya’lam (wide road), or Dre/Te’lam (mule road). A route not simply of tea and horses but of any item that had worth – a route hauling goods up and through present day Burma and Yunnan, pushing up into the mighty Himalayan folds and spires. Two main strands operated – two ancient highways with ever broadening arms that absorbed and drew in traders, ruffians, pilgrims, and still more feeder routes alike. The Sichuan-Tibet route prospered during the Song Dynasty (960-1276) though it is for me, the great Yunnan-Tibet route that holds both the imagination and the taste buds – a route that gained strength during the mighty T’ang Dynasty of the seventh century. Though, the Sichuan-Tibet route was daunting in its own right ultimately my preference for the Yunnan route was decided by the age of the route, the cultural diversity, and of course by the tea itself – large leafed, grown in Yunnan and potent in taste.

A stunning example of 'Camellia Sinensis Assamica' - Yunnan big-leaf tea. Huge and sturdy, the leaves cover many of the ancient tea trees that once supplied teas to the Tea caravans and found their way to distant lands. This huge leaf belongs to an ancient tea tree near Nannuo Mountain.

This ‘Gya’lam’ (wide road), or Dre’lam/Tre’lam (mule road) that the Tibetans refered to the Tea Horse Road as, gives the whole route a slightly ‘bigger’ feel and a more realistic description. The Tibetans were crucial cogs in the length of the route. Lados (muleteers whose name literally means ‘hands of stone’) of Plateau pedigree were indispensable in dealing with altitudes, bandits and the wonderfully tangible ‘ways of the mountains’. Everything with a need or a market traveled – from medical herbs (opium included), to resin; animal skins to copper products; salt to novice monks and even gifts joined that one great eternal Asian commodity – tea, on its great journeys. The ‘couriers’ required were equal parts warrior, horseman and trusted ruffian. Rugged war ponies from atop the great Plateau made their way east in a kind of informal trade – but the route itself was much more than simply tea and horses. It was a great conduit route of news, mortals and commodities that was one of the great journeys of history – it was an ‘everything’.

Taking a swig of whisky while delivering his memories of travel along the Tea Horse Road an old 'Lado' keeps the more vital elements of the route alive.

With so many ‘facts’ now at hand about the Tea Horse Road, it is the memories and the anecdotes of many who participated along the route that add a zing to the tale. Numbers – raw data – are only part of what makes the story of the Tea Horse Road so eternal. Yes, the tale is of the muddled force that is economics across the greatest mountain range on the globe but it is also a tale of a crucial link of cultures spanning thousands of kilometres and linking all of them with a ‘green thread’. What stimulates and provides a ‘life’ to the route and its almost fabled legend are the commentaries and legends passed on by word of mouth. One of the commentaries we were privileged to take in again and again was about the tea itself that traveled the route – the tea that piqued the taste buds of some of the planet’s most isolated peoples. It was upon our own seven-and-a-half month journey along the Tea Horse Road – a journey that took an inspired and at times withering toll – that the preferred ‘tea’ of the mountain peoples became clear.

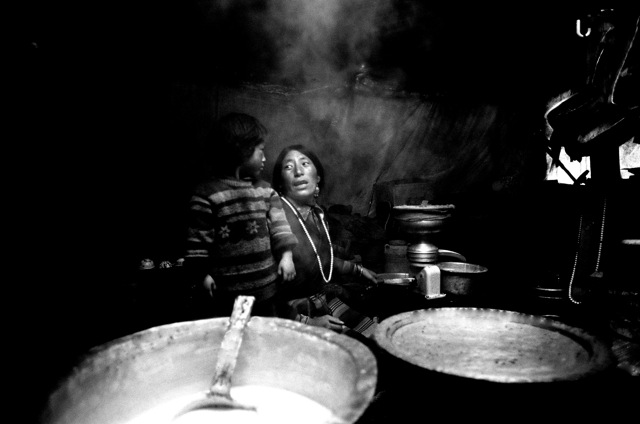

Food, offering, commodity and ultimately a binding gift, butter tea is the equivalent of an offering of life within the mountain realms. Salt, butter, stewed tea and often even some ground barley (tsampa) thrown in, it is nothing less than a meal.

The coarse teas grown in forests of sub-tropical humus forced into tubes of bamboo, wrapped in leaves and the skins of trees to ensure waterproofing arrived to highest market towns on the globe exhausted and utterly potent. Fermentation over the course of months of travel brought tannin levels up and some pungent results. Altitudes, colds, time and proximity to the heat of yak and mule bodies that transported the tea, created a cocktail of circumstances that created teas that would be craved for centuries. ‘Tea’ of the heights, even now, is something more meal than simply beverage. Teas are cooked and stewed for thirty minutes to the point where the resulting liquid is like potent syrup. Every possible bit of taste and stimulant is drawn out. Poured into wooden cylinders with globs of butter, splashes of salt, the ensuing mountain meal is then mixed with a wooden ‘plunger’ in series of ritualistic movements. While this ‘tea’ is known as ‘bod’ja’ or ‘pu’ja’ (Tibetan tea) there is more to the tea leaves themeselves…the ancient Tibetans we encountered enroute all expressed a very unambiguous preference for the tea of Yunnan – tea that they called ‘kabo’ (bitter or pungent). It was tea with bite, tea that hit with a force that withered the mouth’s delicate skin…simultaneously ‘kicked’ the body and blood into gear. This was never so clearly demonstrated as it was in a nomadic community that entertained and hosted us one night upon the highest of highlands.

The blistering rays of a brat sun had long since dipped behind a ridge when we entered a tent in Ala Dho’tok (Stone Roof) within the shadows of the Nyainqentanglha Mountain Range. Entering the nomadic home at five-thousand metres after almost forty-days of trekking, the requisite tea and warmth was offered without question. It was and still is the one absolute offering made to any traveler and it touches the soul (and taste buds) that people with so little offer this ‘exotic’ from afar with such consistent generosity. So valued is tea that it is often shoved nearby to altars – the sublime next to the otherwordly. Once inside the tent a still stunning elder nomadic woman answered my inevitable questions about trade and tea with a smile and some force. Her passion for talk of tea brought all focus upon her words.

Our hostess who waxed eloquent for the days of bitter and more potent teas from Yunnan, near the Nup Gong Pass in Ala Dho'tok

“The tea of jia’yul/ja’yul (what many Tibetans called ‘tea-country’ referring to Yunnan) was the tea that left the mouth happy” she told our group. She also lamented the fact that these teas were no longer available to her remote community. Instead, rough brick teas from Sichuan (around the Ya’an area), lacking both good grade tea leaves or any strength to impart are all that is available.

Gradually it would be tea from Sichuan that would dominate the Tibetan 'market' - though many upon the Plateau remarked on the 'lack of punch' of such teas

Long a fan of the minimal ‘ways’ of the nomads, I was taken with her impassioned but nostalgic memories of a good jolt of potent dark liquid. These words seeped deep into my core, as one of my own ‘worse-case-scenarios’ in life would be to be suddenly ‘without’ a quality dose of powerful tea. With me (and constant companions) were a couple of giant discs of compressed Pu’erh for my thrice-daily sessions of thirst along our own journey. Cracking off a chunk I passed it over to her. Little fires came into her eyes as she grabbed the hunk. Creases of joy appeared on her sun-touched face sending her features into folds. Callused and covered in the toil of her still-busy days her fingers toyed with the dung like shape of as though recalling an old sensation. Tucking it into the fold of her hold-all chupa wools, it was put away for another occasion. Little fuss was made over the gift but the briefest little hint that the tea would be hers (and hers alone) delighted me.

A site that hints at the eternal appeal and vitality of tea - a nomadic clay stove with a tin tea kettle burbling away

Her reaction to the ‘tea with force’ from Yunnan wasn’t at all isolated – it seemed a kind of universal longing upon the Plateau. Unfancied, delivering a punch and a joyful jolt to days at the top of the world, tea is one of the luxuries in world of few. Weeks later after this tea session at near to five thousand metres, we arrived to Lhasa and its notoriously sweet teas (‘ja’ngabo’) – affected by sugar standards from further south in India and Nepal. Sonam – mountain man without equal and still a friend with unambiguous views – looked at me at one point with a tiny glass of sweet tea nestled into his hand and muttered “great for a little treat, but not enough”. No, not nearly enough I thought.

Not all tea was destined for delicate pots and ornate ceremonies. Much of the tea upon the Tea Horse Road would find itself as one of the crucial 'musts' within isolated nomad communities, providing far more than a beverage. Here a nomadic homestead near the Sichuan-Tibet border

hi, Jeff … your site is so beautiful. Thanks for sharing these amazing images. I imagine you have millions. Hope you’re doing well. What’s next on your life’s planbook?

Hi Lauren,

I know you relate to these images…great to ‘hear’ your voice from afar.

Next, sourcing tea for an upcoming personal venture…tea is always in view. Preparing for an upcoming two week ‘kora’ around Kawa Karpo – one of the holy mountains of the Buddhist world.

Winter is settling in here….

be well,

Jeff

Jeff – Your comment above of “sourcing tea for an upcoming personal venture” is intriguing. Hopefully, you will be sourcing teas for the retail market, either directly or though a third party. There is so much poor-quality tea (and high-quality hype) on the market that tea from you would be a very welcome offering indeed!

Best wishes,

Peter

Will keep you in the liquid loop.

Jeff