A sight and activity repeated twice daily – milking. Tibetan tents and compounds are usually erected facing east…and the rising sun

Informality amongst nomads, and that feeling of immediate and informal acceptance comes from their own necessary and inevitable informality amongst themselves. Sickness, births, joy and efforts are shared in real time every day of every season. Bonds are strong and all is shared, and though disputes arise, the lines of communication are entirely direct and open – otherwise the way of the nomad would crumble quickly. Intimacy here is perhaps unromantic in the western sense but it seems to be entirely ‘intimate’ and authentic.

Michael and I wander out of our tent and onto the crunch of frost on the grass. We have set up our two-man tent just outside of the main entrance to the family’s. Space is needed for the crush of bodies that our group of five brings.

Sun (nyeema) and its rays have only started touching the stiff grass but already the yak have been let loose off of their tethers and are making their way off to the highlands, munching as they go. A few are still tethered with yak wool bindings around their legs as hunched bodies milk them. Smoke streams out of a dozen tents, wafting up-valley slowly – no winds have yet touched us. There are few silences like those that the nomads wake to every morning and speed means nothing – here everything is paced according to ancient memories.

Chura, the sour yak cheese of the nomadic areas, lies under the sun. This was and still is often used as a form of protein and added to butter tea

Songjem’s family moves far less than some of their nomadic brethren upon the plateau. They have three dwellings all within ten kilometres of eachother, and their summer and spring areas rest within the same valley corridors. All of their ritual movements are for the benefit (and driven by) their precious yak herds and their frugal needs. For Songjem, the fact that his children and their families are so far is something sad, but there is no hesitation in his voice when he affirms, “yak needs override people’s”.

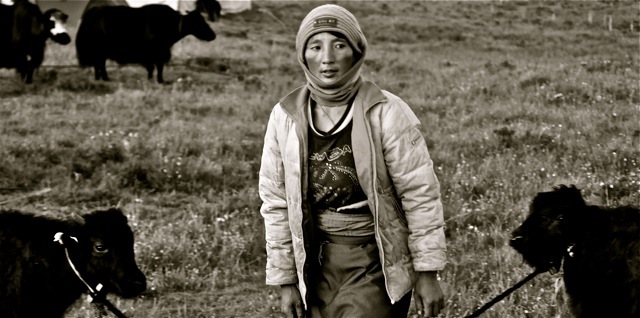

A nomadic woman’s life is made up work, sleep and more work in a schedule that would break most mortals...but only most

Huge yak herds are the norm here in Gansu and much of nearby Qinghai, with hundreds of yak making up a herd or group. The larger the clan the more yak are likely to be present and the more yak, the more sources of income for the nomads.

Caterpillar fungus, an medicinal root called Beemu, chura (yak cheese), yak meat, yak wool, and sheep and goat wool make up the bulk of what can provide revenue and all of it is seasonal.

What has repeatedly refreshed and inspired me over the years (though the nomads themselves often don’t agree) is how they know exactly what is and isn’t important in their lives – there are few ambiguities. If a child is chosen to go to school, and one or more aren’t selected there is rarely dissent. In fact there is sympathy with the student who must leave, as they “will be alone and away from us”.

Every day, without fail, bodies emerge morning and night to set loose, or tether the herds. Even amidst herds of hundreds the nomads can determine how many (and specifically which) yak are missing in minutes

During a communal family get-together, Songjem stretches out his languid body in the grass and the entire clan blends themselves into the turf. Words are sprayed out with that warm nasal sound and undulating tones. Even their words, spartan and frugal though they may be, are infused with passion and meaning.

A young nomadic man, along with Songjem in the background corral the enormous herds of yak and count them

There is a rhythm here in these grand spaces and a feeling amongst the nomads that though there is much that isn’t understood in the world beyond, there is an absolute understanding of the elements within it…and when they don’t comprehend shifting weather patterns or a plight, this is where the ‘fates’ and the spirit world arrive to assist.

Yours truly indulges (which later turned into over-indulging) in some sho, the local curd-yoghurt specialty, where the tongue becomes the instrument most active.

Songjem in his effortless and very real eloquence sums up one day’s end when I ask him about what he thinks the future holds, “the health of family, yak and our way of life – that is all I can worry about”.

A fascinating glimpse into the lives of these nomads. I find much to learn from their outlook and way of living. Thanks Jeff!

Best wishes,

Peter

P.S. Nice pic of you doing “the sho slurp”.

Peter,

Yes, well the ‘sho slurp’ is now part of our newly formed vocabulary of the hills. I too hope that the nomad’s lives will continue to inspire…I wish they themselves knew of the value we find in their ways of living.

Jeff