Baima’s empty valleys and snow shards stare at us. We have left Benzilan behind and ‘Ngawa the Machine’ is no longer with us. Mountain air now thankfully dominates the heat infested valleys and the lethargy that heat brought, gives way to sense-sharpening cold winds and dry thumping pops of air pressure fluctuations. Baima (White Horse) Snow Mountain doesn’t get much attention but it is lofty and holds beautiful angular lines of snow and stone. It is a gateway of sorts to what lies beyond. Songjè too has gone back home, unwilling to stray so far from home upon trails he is unfamiliar with. Yanpi, Tenzin and I trudge forward.

Yanpi has gotten stronger as the journey has progressed and Tenzin’s feet are on the mend though he is not sleeping well. For me the cold is waking me up and pulling me into its big hug with a dose of stimulant bite. Cold can invigorate and resuscitate the senses and soul. We are getting closer the grand width and shrieking power of Sho’La pass and in my mind’s eye I can see it beckoning like an ancient homeland.

We pass the grandeur and gleaming power of Meili Snow Mountain (Kawa Karpo to locals) and its stunning ‘wife’, Metzomo. The two sacred mountains stand far from eachother as though still figuring out whether their own union is one that is desirable. Kawa Karpo is said to have a deity living within; a warrior on horseback and a slick little moustache, who changed his warring ways and attained enlightenment in a single lifetime.

To test his ire is fatal, it is said. To climb upon his sacred slopes is to test those fuzzy concepts of fate We decide not to test him. It is odd that we rush past such majesty, but our human desires lie on a hidden pass, not the overwhelming vistas of the snowcaps. I feel the mountain’s outright beauty grip and tease me but ultimately my thoughts are with another. Always the pass draws me, draws us, like a stone beacon of power.

It takes us almost three days from Benzilan but we arrive to Sho’la’s base town of Merishu and a local horseman awaits us. His mule looks like it has been through every war ever fought with scars, gashes, and old wounds decorating its skin in a patchwork of lines. The horseman himself is a squat, powerful man with a wide face who tells us of a lifetime of mountains and the heart condition it has given him. He is a friend of a friend of ours. We’ve been told he is a slow but steady traveler who will not push his mule, which suits us just fine. Speed at this point has no interest, but progress does. We are here and in two days we’ll reach Sho’la.

An elder watches our team prepare. How many such preparations has she witnessed. She tells us “many”.

It lies through a westward series of switchback valleys of stone, then south and then west again. At times I feel like I can hear the pass and its howling winds. At one point Tenzin tells me bluntly “your senses and desires are running too far ahead”. Whether he refers to the feelings I have for the pass or for life in general, he doesn’t clarify, but it matters not.

There are three informal entrances that ascend to Sho’la. We will take one that is more direct but less used. There is little talk as we prepare but our horseman’s entire family (all women) come out cooing and making sure that his care package is bulging with goodies for his journey. It slows me down and impresses upon me what travel here is. Though he will not travel far and will only be gone three days there is the worry that people who live intimately with the land have. The mighty elements and stresses of the geography here are tangibles dealt with on every single day. They are not distant concepts but rather they are the ‘here and now’.

A moment of rest brings the deep bond of our horseman and his mule into a closer focus. They are bound because of their history and because of the need to be bound

Our horseman’s daughters and wife implore us all to be safe, telling us that there was an old woman and young girl recently found dead along the route. They had fatigued and frozen to death in an embrace just beyond the pass. Even now, the Pass’s power can dictate how one’s days end.

Pilgrims and hunters still use the routes, but the days of trade and caravans have sadly passed. Many pilgrims still underestimate the pass and for locals it has long been known as the “Pass of two faces”. Hunters never underestimate the forces at work in the height; a visual delight one moment, and a sky-fueled fury the next. Every year pilgrims die and even locals occasionally find themselves locked into disorienting blizzards which are rarely forgiving.

On previous journeys here I’ve always had crystal clear dreams during the hours of dark. They are the high altitude dreams of intense colour and sensation and the region has always left an imprint upon me. There are places that hold some of us for whatever reason. They draw us, hold us, and whisper and scream at us, and then, without a fuss they let us go. Sho’La for me is one of these places.

We move at last. It is late morning and limbs are slightly fidgety, as we want to begin the ascent. Yanpi shows quickly a natural ability with not only locals, but with the mule as well, issuing out “clucks” and high whistles, which are responded to instantly by our four-legged mate. Tenzin’s attempts to urge the mule on with shrieks and loud yells seem to piss off our mule more than anything, and at one point it simply stops and looks back at Tenzin as if to communicate that one more such unnecessary outburst and it will refuse to budge…or worse. Yanpi in his quiet sarcastic tone tells Tenzin that he should worry about the route and leave the mule to those who know.

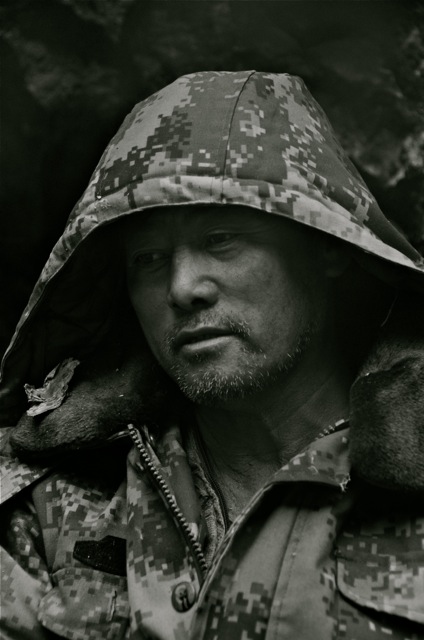

Our horseman studies the sky for signs of changing conditions. This habit was something repeated dozens of times daily

The horseman is a gentle bull who rarely speaks but keeps an eye upon the narrow slit of sky above us. The valley is tight as we climb and the sky’s language is studied for good reason. Every slight change in wind, every discoloration and tint of the sky is studied, smelled and studied some more. As the altitude steadily ascends, weather’s unpredictable variances mean far more to our own endeavour.

We are gobbling up metres, crossing and re-crossing a voracious, ice cold mountain stream. At times I speculate upon the traders of the route who travelled so much of their lives on such paths, and that they must have been sublime philosophers who balanced their faith in the fates and in their abilities with near brilliance. One must simply endure. On the other hand I wonder if many such muleteers must have simply been desperate and had the constitution for such ceaseless travel through elements.

Priceless, relentless, valuable and obstinate, our mule is an absolute necessity, though its role and use in the mountains has been downgraded with the advent of vehicles

Our eventual camp is off the part within a small basic of protective rock. It has been used by hunters and locals for centuries and looks well-worn and almost cared for. We choose it because of its protective shroud of stone preventing winds from hitting us, and because our horseman tells us that it is as far as he will ascend on this day. We have ascended 1800 metres in good time and take our time setting up camp in the dimming light.

One of my nightly habits is to soak my feet in the blistering glacial streams. It acts as both a slightly masochistic tonic and a cleanser that leaves me simultaneously feeling intense pain and a kind of puritanical pleasure. It takes only seconds until the bones in my feet feel as though they have been pulverized.

Back at the fire Tenzin is at it again, making us his ridiculously sweet coffees. Somehow this little pleasure of his seems to make him right again. He is a man who needs his little treats to stay sane, which in turn keeps the rest of us sane. A small amount of coffee, followed by a long dump of white sugar and it is ready in our tin cups. I refuse, knowing full well that it will send me into a night of tossing and sleepless introspection, that I don’t need. Tenzin pawns off my cup to the unsuspecting horseman and I wonder if he knows what he is about to consume. A loud groan of carnal pleasure escapes from Tenzin as he takes a long and noisy slurp of the muddy liquid. Yanpi is his usual efficient self preparing our camp and taking a little amusement in giving Tenzin orders to set up our minimal cooking gear.

Yanpi is a bit of a perfectionist in his languid way and in an informal way, the cooks on these expeditions are always the bosses. Dishes must be spotless and the area surrounding the campfire must be ordered and tidy. Yanpi detests messes of any kind which differs from Tenzin’s rather casual approach to organization. It has become a running joke that Tenzin can never find what he’s looking for in less than 20 minutes. Another little habit of his is that he never remembers to do up his various zippers. Pockets hang open spilling items over the ground and it is usually when he bends over that we all collectively hear the “clunk” of various things falling to the ground.

Yanpi has managed to save us some green veggies for dinner. A huge soup with both known and unknown content is fired up on our fire and we tuck in, saying very little. Our horseman disappears mid-dinner without a word taking only an axe and a long wicked looking knife. He has no headlamp or flashlight at all. He simply walks off into the cold forest. We look after him wondering and even his mules seems to stare out into the dark for its master.

Twenty minutes later he returns dragging neatly cut bamboo stalks from “up on the mountain”. He explains that it will be a nourishing treat for his mule. He sets the vividly green leaves and small stalks on the ground near the mule’s tethered ground.

The mule eats up his sumptuous green treats paying us no attention at all. We stay up late and the coffee takes a firm grip of our poor horseman, just as Tenzin falls into one of his noisy sleeps.

Sho’La’s bristling edges will welcome us tomorrow.

This post, about people sticking close to home, reminded me of a story my wife once told me:

A group of Europeans were exploring a mountainous part of South America. They noticed that the local porters and guides they’d hired would sit and take breaks at random intervals. After a few days, the Europeands asked them why they were doing this. One of the locals replied, “We are waiting for our souls to catch up.”

Ted,

That need to do things at a slower pace, and to “let things catch up” sums up so much of how they live their lives. They live on the land, understand its every ache and don’t seem to need to prove much.

Love the quote about the souls. Might be that should be a requirement for all travellers, to “wait for our souls”.

thanks for the words,

Jeff