So many sips and times of tea that have made their way into me have been enhanced while sitting in the surrounds and spaces in which the tea actually grows. In the words of mentor and extraordinary pan fryer of leaves, Mr. Gao, “You see leaves at the source and the sips you take will not be the same”. Mr. Gao’s presence never hurt either. Of the Hani people, his home in Lao Banzhang in southwestern Yunnan is one of the epicentres of Puerh.

The gentle man of tea and wisdom, Mr. Gao.

The village exhaled teas who’s prices could astound as surely as they could entrance. It is a village, where on my first visit was still a space of smoke-stained series of wooden panels on stilts, slow mornings, and a space where everyone was in some way related. Around the village then (and still now) were forests of ancient big-leafed tea trees.

A tea taking at Mr. Gao’s in Lao Banzhang, where he sits in the left holding some of his tea.

Mr. Gao’s neat moustache and careful face haven’t changed much over the years. His renown as a pan fryer of impeccable detail and a modulated slow speed of speaking too, give one an embedded trust. He would often repeat those words: “You see leaves at the source and the sips you take will not be the same”.

Seasonal work, tea is. Spring sessions are completely immersive times where families are entirely engrossed in producing the coveted flush of the new year.

They stay with me still as a kind of mantra that links land, people, and that vegetal narcotic that has long held me. Those words are present every single time I’m in the ‘hands’ and space where tea thrives from soil.

One of the many skill sets of Mr. Gao, was that of master fryer. Here, his hands and bamboo tools finish up a set of leaves.

Perhaps one of the aspects of tea that gets lost in the fury of descriptives and nuances, is the fact that tea – beyond all else – in my realm at least, is an incredibly visceral and tangible thing. It is a thing linked and bound to space and people that contribute to it appearing in front of me. Context around the tea can, for some, transform an entire flavour or experience – the forested origins of the plant and homesteads where stunning teas are served up with little or no pretense. In my own time drifting to sample, source, and immerse into the leaf, teas that have touched me most have been those that have been offered up in rougher settings where tea wasn’t quite yet gussied up in wrap or surroundings of tea porn.

Inevitably, the simpler the setting, the more real and connected the tea experience.

You sat, listened, and partook. Teas offered up by those that make the teas have ultimately always been somehow more settled and less sullied. Tea in these spaces with those that produce it inevitably embody the aspects of tea that I prefer. On rare occasions, a tea can transport the mind and body with qi and beautifully managed hands into the realm of “anything is possible”. On other occasions it is the occasion itself which forever binds a particular tea to a time, a place, and those that surround.

Ancient trees at the source in southern Yunnan bask in a kind of temperate oasis of natural critters and clay-rich soils.

With all of that in mind, and with some soil and seeds available, in the early summer of 2016 I decided to throw some different cultivar seeds into two small little plots of land. Nothing would have happened without the soft coaxing hands and permaculture brilliance of Christine Young, a friend on Hawaii’s Big Island. Apart from a notion to see which seeds would actually take on the dry side of the island, this was a little homage too, to the sentiments of Mr. Gao. I wanted to immerse and be around tea that I’d had some role in; wanted to check in on them when back on the island. Essentially, I wanted to create a longer lasting context and experience with leaves that I might one day consume.

Fast forward to Big Island, Hawaii, and some of what we are growing.

Into the ground went the seeds with an accompaniment of Adzuki beans, comfrey, citrus, and pigeon peas, planted in a random splay around the tea plants to raise the nitrogen levels within the surrounding soils. Oregano (a kind of natural forcefield and deterrent to many of the bugs) went in as well…and soon the earth-bound seeds which were invisible to the eye for a spell of time, became part of a rich, bio-dynamic environment.

Though there wasn’t a Mr. Gao nearby to enhance the gardens with his tales and gentle overseeing or with his wonderful pans, there was a tangible sense of transformation and evolution. Many seeds never produced but with time (that still-magical element that itself needs time to appreciate) many did did make their way to the surface to begin to emerge upwards into the light.

Though our tea rests on the ‘dry’ side of the island, increasingly erratic shifts in weather patterns arrive. The tea, throughout all the stresses has evolved.

The seeds were an assorted collection of varietals to see what what would take in the environment. Yabukita, Yutakamidori, and even something in the Bohea family all sprouted and stretched their stalks and leaves. Bugs, slugs and beetles did appear and in time nibbles were taken, blemishes stained the skin of the leaves, but all of the plants moved forward and struggled through their little episodes.

Throughout the 3+years there was a sense that this was exactly Mr. Gao’s point: that the wait and watching this slow green evolution gave another perception layer entirely; another layer of appreciation and understanding. Early life stress is what the camellia sinensis sinensis plant enjoys and that stress demolished some, but those that made it through that little bit of juvenile angst grew full and lush.

Leaves and buds at the ready for their first infusion.

Late last year and early this year, I plucked a few of the yet to unfurl buds during some mornings when the leaves were dry. Their gentle fuzz was visible on the supple buds and there was promise in their lush little bodies. The intention for this first ever clipping was to create as near to a rough ‘white’ tea as possible. Withering the buds over two full days with a combination of shade and some light sun exposure, the leaves met their last stage in a very low 7-hour heating at 41-degrees Celsius, within a simple plant dehydrator and hummed on the floor.

That first infusion

Then, it was, finally time for an infusion of water. It was that moment that had been building for years and a moment that Mr. Gao would have embraced with the wisdom that he carried in him. Though white tea was something he could barely comprehend, he had already contributed greatly to this 3-year buildup encouraging perhaps a more complete understanding of what tea was at the source.

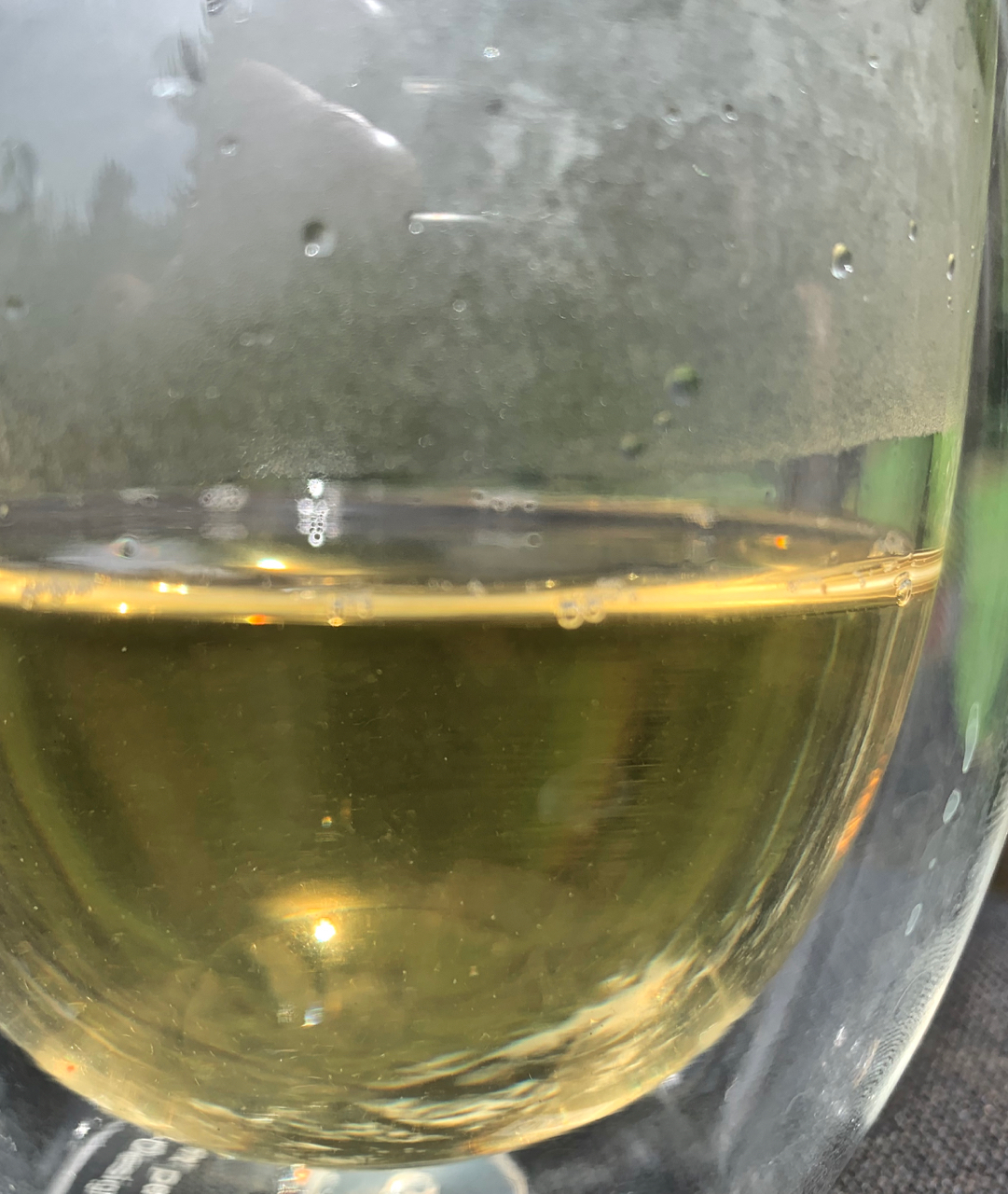

The hum of an oncoming sip.

On a morning of lemon sun, before any food or drink had passed into the mouth, the preparation began. Mr. Gao’s moustache and gentle eyes were there in the mind as I prepped the little gai wan. With some variations in the serving amounts and in the infusion times the leaves put out as they could.

Nectar poured

What worked best for my palate (a palate that doesn’t do many versions of any white tea) was a 7-8 gram serving of leaves for 3 minute infusions using 85 degree Celsius water. I mustered out three decent infusions that played somewhere between a hint of some hints floral with a surprising little jolt of malt.

First leaves bundled and spent. Buds, half buds, and flags after they have given.

It was enough that some flavour was wrung out with something delicate in the nectar that transferred into the cup, and onto my own palate – mild and but present and there was something that caught nicely; something that I’d categorize more as a kind of vegetal burst. The second and third infusions needed slightly more infusion time but they too continued to give something far from unpleasant. Though I describe this as a white tea due to the ‘production’ values of it, it runs close to an equally pleasant green tea. A beginning then and a little toast, to the gentle and immaculate brilliance of Mr. Gao. It will be in his style that I moved forward with these little tea bushes.