Nothing quite ‘scars’ the palate like a magnificent hit of a powerful tea. From that moment forward something has changed and it might as well be an actual mark or scar because it is memorable and it changes everything for all time. Whatever it is that has grabbed the molars, wafted into the cavities of the mouth and nasal cavity, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that from that moment on a portion of the brain has decided that something stunning just occurred, and it is a critical moment that will move decision-making irrevocably when selecting leaves. Something has been activated and there is no real return to anything remotely blasé. Important too is to revisit these monsters of the palate to be part of their evolution. It is one of the eternally delicious aspects of Puerh…that it does evolve and grow with time.

One of the beloved ancients that rest in the sub-tropic forests. They are the providers of something utterly sacrosanct when produced properly.

Beyond fabled names, reputations, and beyond too some of the outrageous hype around teas, a tea (however humble the source and the hands that create it are) can grab a palate as surely as a moment of enlightenment can. The experience of a good tea can happily obliterate all memories of every average/flavoured tea that has ever made it into the cup and mouth and serve to clarify.

He Kai was one of those teas the first time I tried it and there was something slightly revolutionary about it. It lingered in the mouth and mind after having been vigorously advocated by a friend in southern Yunnan. It was a tea that powered onto the molars and cells within the mouth and didn’t relent. It lasted and lasted and never seemed to finish badly. In the words of a good tea drinking mate, it was “haunting”. That it was. In subsequent samples it remained just as striking over months and then a year it evolved in small ways but it retained its enamel challenging strength while never straying into the ‘too-bitter’ or the dreaded ‘sour’. It was a tea that carried deep throngs into the mouth and finished clean. Of course, there was too the fact that a particular family had produced it by hand from pluck to wringing out the last bits of moisture.

Bordering the fringes of the famed Puerh Ban Zhang region in southwestern Yunnan, these gentle areas (and its teas) of the Lahu, Dai, and Hani minorities frequently gets missed. Missed things are often very good things because they must continually develop rather than presume anything. Koreans have long found value in the teas of He Kai and been fans of its qi (energy or force) whereas locals are fans of the ancient trees in particular and its long flavor notes. Ancient trees (older than 100 years) offer up flavor notes that can either be maintained – and even enhanced – or hands that produce them can desecrate them. No tea is guaranteed status unless the hands and knowledge are equal to the raw materials. My He Kai experiences had run the gamut from Dai people’s offerings to Lahu and back to Dai. It was their leaves and their procedures that rang all of the salivary glands for me.

The place of He Kai is a wonderful kind of crucible of indigenous cultures and epic tea growing regions. Known for gorgeous parasitic orchids (rumored to enhance some of the ancient tea trees as they fuse onto the trunks and branches), mountains, and clay-heavy soils, it remains a tea coveted by drinkers year after year. It hasn’t always been a place of consistency but its teas have improved to a point where one can start to depend on independent families to provide a little bit of predictable pleasure. It is a danger to depend but, for a drinker, it is a sacrosanct pleasure.

Years had passed since I’d first wandered into the region with a friend covered in dust and craving a sit down with tea. Southwest out of the tea collection point of Menghai in southern Yunnan, we turned off into the watermelon fields shielded with plastic at the village of Meng Hun and towards the Bulang Mountains. The spine of the Bulangs was a kind of elevated holding line for the valley. Arriving to a Dai homestead we were confronted with tea’s ever-present wafts, shapes, and necessary tools. Tea ran the entire place and harvest seasons were a time when every mortal being was involved somehow in some stage of tea’s collection, production, or sale. Upon our own arrival, tea was barely mentioned in the first 24-hours. Firstly, one had to eat, meet, sip some of the tea before meeting more and sipping some of the potent local firewater. I was happily dragged through homes and nearby villages as the local Dai New Year’s celebrations were in full swing.

Villages and sources of tea are precious things as it is here in moments, meals, discussions and wanderings that the leaves that are consumed become physically linked to the land and its people. A visual and very tangible line from source to sip is made visible. Untidy to some, many of the villages (that appear as forlorn little pods amidst the sub-tropical forests) will produce teas of such divine maturity and strength that it is scarcely believable. In such regions there is too, the predictable other side of that coin: the pilferers, pretenders and charlatans. Pristine, ultra-clean and smiley places can create veritable messes of a particular tea.

Over the course of years, multiple returns for meals, purchases of tea, episodes of incorrectly frying leaves, and repeated conversations, I’d come to feel deep gratitude to be able to return again and again to a slightly off-the-grid village that consistently produced tremendously powerful teas. Teas that please are all the more pleasing when there is a tangible reference point beyond simply a name. This is when land and geography – along with the imprints of smell and feel – are associated with a particular tea and experience. In such regions, such tea zones weren’t so much tea fields as they were chaotic orchards and forests that spread and ran entire mountain sides and plateaus.

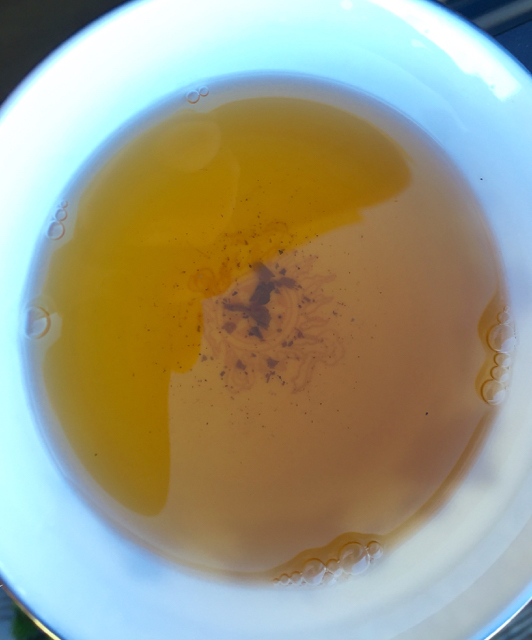

My own palate was recently reminded of He Kai’s graces and fervent power when some of the leaves from a wonderful 2014 harvest were revisited for a slow sit and sip session with the leaves, some water and time. Two phrases were mentioned in relation to this tea long ago and I carry them around in my head whenever I think of this tea. One phrase was “smooth force” and the second was it “lingers for hours in mouth”. In this most recent bit of sampling, it did these two things beautifully. Though it has smoothed slightly in the two years since it was harvested and created, it still carried its distinguished power everywhere it settled in the mouth. Bold and deep, this He Kai adheres to its original line and it is here perhaps that a tea reveals itself in its truest form: with time. Tea needs time; time to sip, time for the tea to develop and it needs time and care to produce it. After two years the tea was still fixed in its strengths with only soft touches of change enhancing it even more. With the first sips my own palate could feel those first times of sipping and conjure up images and smells when I first shared some of the leaves.

Upon re-sampling the 2014 Spring version, the leaves still carry their tang of pungency and urgency and it is in this magical ‘urgency’ that this particular tea shines in a green glow. That little sampling takes place one morning before any food passes into the mouth, and before the synthetic chemistry of toothpaste touches any enamel. It is the first infusion consumed (no rinsing) and first substance that passes into the lips for hours. Every few months I had inverted and shifted the loose leaves so that air could touch and run through even the most tucked away clumps. Dry circulated air is the lifeblood of Puerh teas, unlike so many other teas which require absolute vacuum sealed, air tight containers. Its’ powerful long leggy flavors refuse to release their grip on the molars, even long after the essences have passed smoothly past into the gorge. The volatile elements that contribute to a tea’s flavor are potent but rarely harsh in older tree’s leaves and with competent withering and frying in clean zones some magic happens…and it remains happening.

Some wonderful vegetal astringency – and that vital urgency – still lasts and that is largely to do with polyphenol family which includes flavonoids, which imbue the end buds and leaves on a tea tree. Though the leaves alter with time and procedure, they ring true with my memories of He Kai’s strengths. I have little notes scribbled onto a little piece of paper from long ago sipping’s. That paper remains tucked in amidst the leaves consistent to the first detailed notes about the tea: “persistent”, “powerful”, “long impressions. The notes get an update with the words “like a long walk through the mountains”. It is the long walks that remain nicely hiding the little strolls.