So much of what is good and cherished in my days is both deliberately tea related and in some wonderful cases accidentally tea related. Days into ‘The Glacier’s Breath’ expedition tin cups are held in a large semi-circle of bodies between Himachal Pradesh and the remote Spiti Valley in India’s great western Himalayan world. Tin cups are sipped and ears are listening.

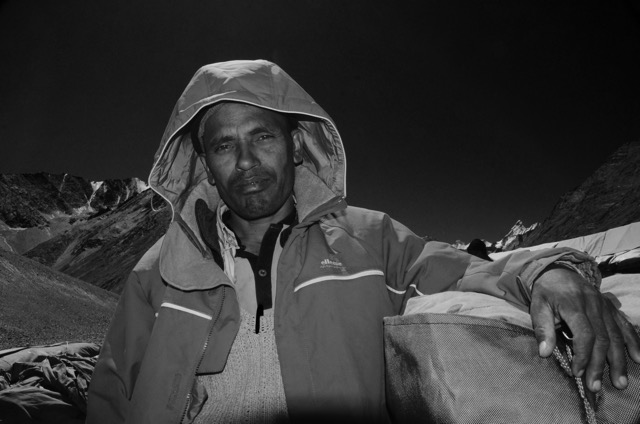

Winds have shifted but here on this afternoon they are starting to bludgeon a bit with winter very close by. Our team of Nepali porters from the west of the country have already begun to show their character and spice and we are just days into this journey into a remote valley of Himachal Pradesh to visit a seminal glacier is Asia, Bara Shigri. The porters are all from the same town their leader is a rugged powerfully built man wearing galoshes and a baseball cap simply reading “OBEY”. Even he Rajesh, though listens intently.

Sixty-eight-year-old Biari Singh with his Kullu coloured cap sitting cross-legged with our entire team sitting and standing around him. He has a substantial audience who watch and listen. Seven porters, 4 of us mountain team members, Debra Tan, who is a water influencer along with two others sit pretty much rapt at the old shepherd Biari.

A tin cup of sweet ginger milk tea sits in Biari’s callused hands as he speaks about water and the glaciers and the ice above (called ‘zeerun’ locally), and how these elements of the same compount are increasingly speeding their disappearance from the white peaks above. Our resident sage and old friend in any mountain endeavor, Karma (who doubles as many things but most vitally our esteemed expedition cook) watches quietly in his own version of a cross-legged perch. Here, like so many of the great earthy places, tea is offered as the perfect accompaniment. Time to sip, to share, to commiserate and simply commune – tea aids all of this. When asked about wolves, Biari shrugged and said something about them being clever but predictable. A more recent event hints at two-legged mortals being far worse than the suvialist the wolf. Biari admits that during a recent celebration (and the ensuing day of recovery) with other shepherds, 20 of his goats were shoved into a passing lorry on the lonely road and absconded with.

Biari speaks of a life of sensory witnessing. Fifty-five years of shepherding sheep and goats in this Chandra Valley, living in stone huts and buzzing tents have given him a perspective of birthing calves, creatively destructive wolves, floods, blizzards and thieves. He now speaks of the way water has increasingly become something rare, unpredictable and ultimately lesser. It is late in the season and within the next week or so every shepherd and his meager possessions and newborn calves will exit the great valley to leave it utterly devoid of mortal life for the winter months.

“The wolves haven’t changed. They still come out of that valley”, his arm strays to a western wedge of valley. “Water and ice are disappearing though. Water is everything here and the nearby Chandra River isn’t the same as it once was”.

The Glacier’s Breath Expedition was conceived not simply to take a trip and guess about what might be happening in the mountains. It was born of a desire to return and compare a previous visit with that of one two years ago, to interview the stewards of the land like Biari, and to see first hand how the precious mountains and their freshwater springs, glaciers, and rivers – which provide for over 2 billion people – are changing. It is to – in simple language – document in real time the vast but undisputable supplier of fresh water (the mountains): the Himalayas. The Bara Shigri Glacier is our first stop on a month long journey, and this long tongue of undulating and often brutal moraine and ice tunnels is as powerful an introduction as any to the world of ‘ice’. This is part of the Himalayan landscape and the increasingly vital ‘Third Pole’. The Himalayan headwaters are the providers of much of the water that courses down into the Ganges and beyond, and this expedition will attempt to make the distant bodies of ice relevant and give them a presence in the mind beyond that of simply a body of temporal fluid.

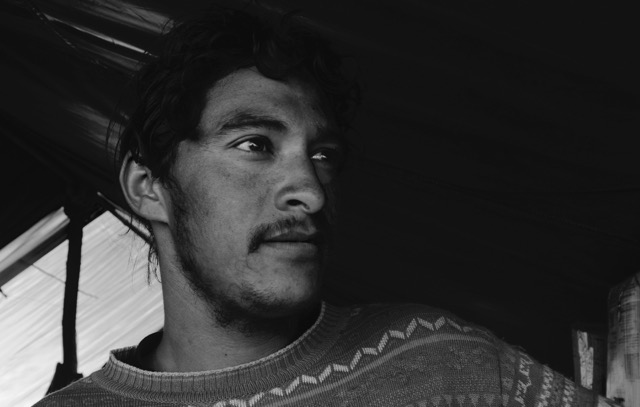

One of our fiercely devoted porters Loutish. Silent and wearing red at all times with a steady pace, he was one of the stalwarts.

At the moment it is the sun-blasted features, the impressive whiskers, and tales of Biari Singh that entrance. Many across the Himalayas have echoed his tales and concerns…those without degrees or access to data. They are the observations of those who live most of every breath of their lives in and with the land, on it and depend directly upon it for their livelihoods. Their motives are those of beings who need the land, love it, at times detest it, but ultimately know it. Precious voices that are rarely consulted and yet have the direct kind of speech that leaves no doubts…these voices also have a thousand years of passed knowledge in their blood. Their bodies have been lined and bowed by the proximity to the moods of nature, and their memories and minds are etched with every season.

Debra Tan is along on the journey, and someone vitally interested in the future of water policy and the very sources of water. This long journey for her began with a desire to simply be amidst water’s present and future and away from her office in Hong Kong. She has joined to hopefully widen the journey’s results and intensify the findings to those that can decide upon what happens with the precious resource. Water is still a mere turn of the faucet away for most but times are changing and the world of water looms large in all aspects.

Bara Shigri, the great long glacier off of the Chandra River in Himachal Pradesh is known here simply as ‘Big Glacier’ in local language. It awaits…a crumbling mass of rock-studded moraine framed by great white peaks, crumbling stone walls of copper and grey, and a howling river valley that never really stills. On the road to Spiti further north east, it is off the road from Manali to Leh, Ladakh, and remains one of the many valleys that is simply passed by.

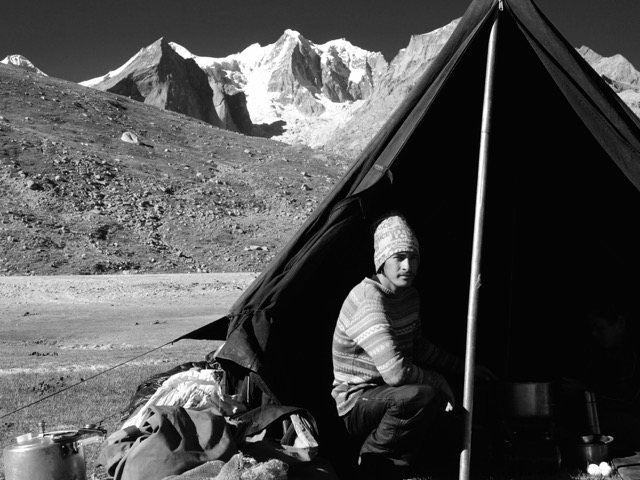

Two days later we have entered into – and onto – the glacier. The porters are epic but cautious. Moraine melts have set off unsettling shifts, landslides and even now there are the echoed thuds of rocks plunging and deep groans of the ice way below shifting. The porters little bodies lean into their loads and they move together in pods taking frequent breaks and singing through the slogging. One mantra I’ve long kept close in the mountains is “when the porters are happy and when the cook is great the journey will be a success”. Cooperate or perish is still very much one of the great laws of the mountains.

The day’s journey that will take us deep into the dark mass of ice and it will take almost 40% longer than it did two years previous. Kamal and Purun are both recently through the advanced mountaineering course and are powerful and swift guides but have the practiced patience of those willing and trained to wait. Debra finds the going extremely tough and Kamal has been given the task of keeping her safe. He does this silently but stays close like a blanket. Get Debra up into the mountains is the mandate and this will need patience and many eyes.

Karma and I become confused as darkness hits us on the trail as the camp we ‘knew’ hasn’t yet been reached and mountain dark clouds the sky. It is another of the aspects of the mountains that remains something very much of concern: not the change itself but the speed of it. My concern is that with the changes in shape and geography that we’ve actually missed our camp side and have passed it.

Moraine has shifted and temperatures and the resultant sliding masses of stone that reside atop the ice have reconfigured the icescape significantly in a short span of time. The journey we knew two years ago is not the journey we now know.

Camp when it is finally reached is an island within the valley and it is a dark and windy world that awaits. It is aday that stretched almost 12 hours. Though the concept of ice is usually one of crystalline clear perfection, the of trekking that we’ve undertaken has been over grey stone pathways, dirty ice, and dust fusing into temporary ugly little puddles. Ice here envelops all and it is this very envelop that is our concern. Vast panels of rippling white ice hang at the edges of the moraine in stunning beauty reflecting moonlight but beauty is very much secondary as reaching camp for all of us becomes almost a spiritual experience. Already this journey has morphed.

Karma’s ‘magic tent’ is in fact our kitchen, dining room and sleeping quarters for never less than three bodies. It is slightly disconcerting when one arrives in a place that is intimately familiar but has somehow been transplanted. It is that feeling that Karma and I share. We stay silent but there is in us a slight apprehension. Tents are up, the winds blow a last little gust and then all is silent. We are upon the ‘Big Glacier’ and Karma’s magic dinner awaits.