Chura or drying yak cheese curds under the sun. High in protein content these ‘pellets’ are often added to butter tea.

It is northwards into Central Asia and the old kingdoms of Turkestan that beckon but borders now are things of great sensitivity and we are heading south again. We’ve headed as far north as we will be permitted to go. The mighty heights have long been places and playgrounds of the powers. Strategic, and otherwise, the Himalayas have rarely had any say about their fates. It is a morose and slightly unreal feeling that this journey is winding down.

The people element of our journey – always vital – is once again dictating where we go and now we head to a wind-blasted bastion of ferocious elements and a very mortal holdout to the modern world’s attentions: the lands of the ‘ndrog’ba’ (nomads). Misunderstood, and both admired and criticized by an outside world that knows little of them, the nomads were the traditional source of pashmina wool.

Both Michael and I had long been fixated on the nomad’s enduring strength and vibrant warmth. Successive journeys in past years through their domains had only served to reiterate their simple understanding of the land. They mirror closely the mighty lands that they called home in all they do and they have never forgotten to listen to their lands. For all of their great strengths and appeal it was (and still is) their utter warmth and graciousness amid such fierce surroundings which had long held me to them.

As we head south again through Leh, this last bit of journeying that we do marks a physical end to our expedition. The grinding is almost done but it never sits entirely well this feeling of ‘an end’. Somehow it is a lie. Our destination is one of the great sources of pashmina…the beginning point and origin of wool’s journey is our finishing point. It is fitting in some way. The notion that pashmina – a craved luxury of the distant and mighty centres of trade, of culture, of esthetic development…the fashion houses and wardrobes of those with ‘everything’ – comes from a land of such impetuous and rampant natural force, seems perfect.

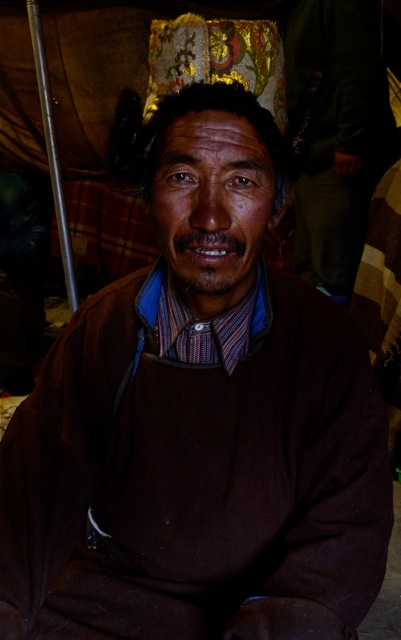

The community that we seek and eventually find is a carved out valley at over four-and-a-half kilometres into the sky. It is a land that has been scrubbed down by winds and nothing remains that isn’t attached to the earth. Everything that hasn’t been blown away by the winds, is here to stay. Landscapes and peoples here have been carved into angles. Surfaces of the living and inanimate have been chiseled and callused. The people’s features have been lined and leathered, voices are hoarse with a lifetime of fighting the raging air and cold.

A nomad’s tent is the domain of the matriarchs and they alone. Woman’s role in the communities cannot be overstated.

‘Community’ is a difficult word at times but here it seems absolutely correct. This is entirely ‘communal’ this collection of 15 or so tents, but it feels like a sparse sprinkling of life. Tents that shudder hide the beds, the fires, and part of the interior life of these great movers of the mountains. These are the remaining homesteads where not so long ago there were three times as many families. This life-style is being abandoned and at some point it will simply disappear.

Karma and Kaku are as curious and carefree as kids and slowly the small and almost shy community comes out, in one’s and two’s, to greet us. Stares are gentle stares. Smiles are genuine smiles or at least that is what my sun-blasted eyes choose to see.

Yak, goats, – and most men – are absent from the community. They are either “away” sourcing supplies, or out with the herds in grasslands a valley or two away.

Sun bombs through the clouds, once in a while lighting a different world than the dull grey sheath of winter coming…and winter is without any doubt coming. Winds come at us and funnel into the sinuses and these winds carry the promise of snow.

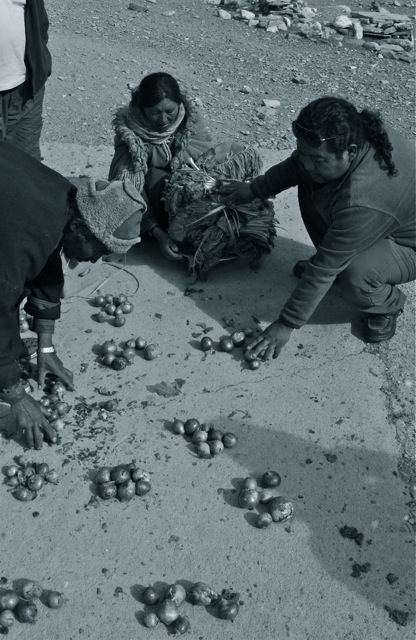

Layered up in thick wools, smoke-stained tuques, and smothering scarves, women sit on rugs weaving on ancient looms that seem perfectly imperfect. Balls of yak wool sit beside them awaiting their turn. It is timeless scene apart from a bright coloured thermos. In these communities, our strange appearance is quickly dealt with as hospitality is offered up and the old adage of the mountains “cooperate or perish” is once again proven. Who we are isn’t so important and this idea of ‘foreignness’ is not a huge one. We are travelers who come gently and all we wish is to observe. We have brought extra supplies to share as to come empty handed would simply burden. Care packages of onions, greens, and peppers are lined up for each tent’s occupants and slowly a member of each tent comes to take their little haul back to their tent.

Michael, myself and our bright yellow tent are together once again but his time we are amid other tents. Black wool tents. The whole valley, the very lives of these nomads is inextricably bound to wool and movement. Yak wool for protection, for shelter, for warmth, and pashmina – the commodity of all commodities up here – provide enough revenue that they may maintain these lives ‘away’.

Our brat sun disappears and that winter grey comes in with feasts of winds and the odd popping sound on fabric as bits of ice race down from above. I look at our tent thinking of all of the places we’ve put her up and all of the shelter that her thin walls have provided.

I show photos on a computer to the nomads of other nomadic lands. They are fascinated by others who share their ways, but remain out of touch.

The woman of the community who – like so many places of the mountains – are the sources of so much power, scurry preparing the stone holds for the animals. East of us there are bodies coming. Bodies which send dust up to be carried away by the winds.

The day is coming to an end for the nomads and for their herds, and for us. The goats rumble in a wide swath of bodies, accompanied by their hulkish black mates, the yak. All of the precious wool comes forward as the light in the sky begins to fade. Night has come to claim her own.

What a beautifully written and photographed site, while I have visited, never to the depths you have portrayed. Thank you, as this brings back wonderful memories. ~ LC

Glad the memories are stirred and that you took the time.

Jeff