A three hundred degree view taken within the protective walls of Abujee facing the valley that is both entrance and exit point for us.

Many say snow is silent; I would say that snow silences and mutes like few other elements known, but it is not silent. Snow at altitude pops and pricks and it bounces in small booms especially when its good friend the wind hustles it along. The snow around me, even under the cracking blue sky, is being whipped up by the western blasts of wind, is anything but silent as it bumps into anything solid. It hints that at any time it can rise before me and crush me…but that has always been part of the appeal of mountains – their entirely random and wonderful strength.

Before our five bodies, a massive valley splits and divides our vista into two halves of beauty. Our group of five is spread out over a ridge – small black dots on the left slope which descends on a 50 degree angle. We are heading towards the mountain worshipped by Yi and Tibetans alike, Abujee – a circular series of triangular peaks that between them hold a sacred lake within.

Above me Kelsang is scrambling up loose rock, having rejected the snow path I am now on. He prefers the “grip” of dry rock to the unpredictable snow that can send one sliding down to an almost casual plunge into a distant chasm. Sonam (ever competent in these terrains) is ahead simeaultaneaously gripping, sliding and loping making good time on the snow pathway.

Behind, Dave’s boots steadily march and crunch upwards and Wangden, the third Tibetan in our party, can be heard (but not seen) singing somewhere on this great slope. His songs, which are more interspersed shrieks of joy than song, jolt through the empty air.

Abujee remains to this day relatively unknown even to locals of northwestern Yunnan – which is one of the reasons our little group is here spaced out like little crabs on an embankment. This is precisely the kind of mountain that seems to sit just beyond notice, and by a happy extension for us, beyond most people’s interest.

Walled in and protected on all sides, the valleys within the Abujee sanctum lie hidden, only revealing themselves in increments as one makes their way deeper in.

It is said that “Abujee” in the local Yi dialect is an expression of joyous surprise, of wonder, of being impressed. The valley that opens before us is a semi-circular crescent; a gate of sorts allowing access only from this eastern access route into a valley that seems to have been carved. For the Tibetans it is said that when one reaches the sacred lake within the peaks, one can see a divine white yak floating – fantasy or legend perhaps, but the scene unfolding before us is fantastical in itself and exactly why lore and fact up in the altitudes are such close friends. White drapes of spring snow hang over the mountains like syrup. Nothing seems to move except the invisible and shuddering wind.

Still snow-covered a portion of the lake sits snuggled within the peaks, while fresh snowfall smatters throughout the peaks.

Our pack finally constricts into a single body along the shale-covered path; we are at last entering the natural coliseum – the amphitheatre of peaks.

A lake sits under grey ice with only a reckless edge of black water showing on the southern shore. Snow sits, covering random swaths of the mountainside and the ominous streaks where an avalanche has torn up a mountainside remind the eyes that not all beauty is benign.

Nature’s arenas for the senses, whether they be sand based, forest-green, or water rich…all have this ability to silence the tongue and burrow into some part of the being and still everything.

An avalanche scar lies upon the slope – one of the only signs that movement has taken place in the high still mountains.

The Tibetan way to climb has always intrigued me. Gifted with generations of powerful lungs, pain thresholds beyond most and childhoods spent running rampant through mountains, Tibetans more than most, can balance speed with rest up in the corridors of thin air. Sonam exemplifies a style of ascent that I have often marveled at throughout our years of mountain history together. He clamours and climbs with speed, without any elegance whatsoever and seems singularly capable of running straight up (or down) a mountain face, taking numerous short breaks to sit down or collapse for just seconds before jumping up and continuing. He has often said “it is when I am tired that I go faster” – a mantra of slight masochism that well suits the incorrigible and slightly indestructible Sonam. I should know, as Sonam and I were part of a team that spent 61 days together trekking the almost 1,500 km’s from Zhongdian in northwestern Yunnan to Lhasa. It was along our passing of the Tea Horse Road that Sonam’s legendary status was formed.

He is at his best when laden with packs and stress – it is here that he shows his magic abilities. Today, he is stripped down to wools, with his fleece jacket tied around his waist. In his hand he carries juniper for burning when we reach the top to thank his gods and the divinities that preside over the mountains for our safe arrival.

When we do reach a natural bluff that sits within the greater valley, winds calm briefly before firing up again. Sonam, Kelsang and Wangdu scream their thanks to the mountain deities that we have made it and get down to the business of unsheathing the Wind Horse flags. Wind flags need their namesake, wind, to be of true use – billowing and flapping in a maze of colours, fluttering out their messages to the heavens.

Wangden and Sonam wrap prayer flags around a sacred worshipping site within the view of the mighty peaks. Pilgrims will often adorn trees, lakes and stone piles with offerings. One of the animist principles that has remained.

Lunch is a simple affair of chocolate, barley bread, hunks of yak cheese (abee) and tiny homemade doughnuts. Strong tea chases down the sugars and we sit in a kind of silent praise. These spaces offer up the chance to marvel, to contemplate and to feel and tangible impact of one’s efforts…and the ensuing silences and fierce winds are the rewards of the day.

The sun burrows and pummels into all surfaces, unrelenting. Here gentleness is measured in small parcels, as all objects must contend and endure the elements.

Not a thing moves but the new and old prayer flags which flap like lonely beacons. Our friend the sun slowly swivels heading west and all for the moment in this little pocket of Abujee is well.

Later, while heading down the same errant snow path that led us up, Sonam starts whistling and humming – one of the few signs that our resident stoic is contented.

Great article, as usual, Jeff!

You mentioned that the lake was sacred. Do you know why Tibetans consider it to be so?

And once at the lake, did you (or any of your party) catch a glimpse of that “divine white yak”?

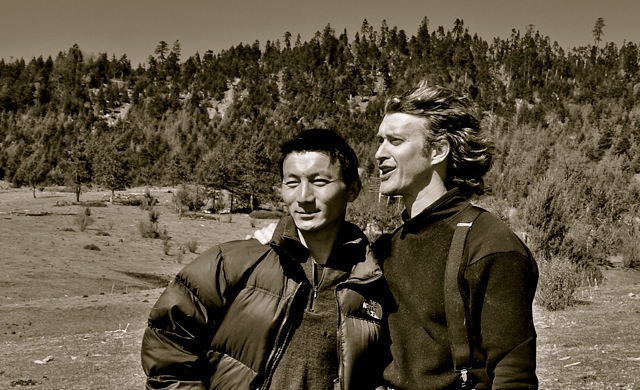

Love the last picture, of you and Sonam. The expression on your face, as well as the wind-swept state of your hair, are wonderful !!

Best wishes,

Peter

It is my pleasure to say you that all of your articles are superb and I really love the way drafted each of the sentences. You will be rated 8.75 out of 10. Brilliant work,Get going. Your sense of grammar is just superb. Carry on the good work.And yes i have digg your site http://www.tea-and-mountain-journals.com .